It’s impossible not to feel admiration for nature. Mountains, rivers, canyons, their topography and verticality, their forms and colours. The majesty of canyons is something truly impressive. Every canyon has its own unique features and charm.

Whether you are looking at them from without or within, canyons are places that make you feel. Either way, it’s a special feeling.

Canyons are places that make you feel alive, joyful, inspired… They make you appreciate life. And once you’re inside, you forget everything else going on in your daily humdrum. You simply enjoy, focus on what you do, and escape… you become free. Their immense beauty naturally leads to meditation. They are places where you can find your absolute peace of mind, but where you can also find utter chaos.

Canyoning, Canyoneering, barranquismo, torrentismo…

Those of us who love the sport know how fascinating, crazy and amazing canyoning can be, with its range of colours and forms.

The wide range of disciplines encompassed in canyoning (such as hiking, white-water techniques, free diving, climbing, down-climbing, specific canyoning techniques, survival skills, advanced route-finding) make it a very interesting sport. The mix of physical, mental and technical challenge is also part of this sport’s great allure.

All of this, combined with the unique variety of forms and colours found solely within canyons, leads many of us to carry heavy packs into the wilderness, spend countless hours soaking to the bone and even go so far as to risk our lives.

Canyoning is leadership, teamwork, self-motivation, it is about learning to trust yourself and to trust every member on your team; one can never forget the beautiful and epic moments spent with our teammates. There are so many things that make canyoning a truly wonderful sport. It’s an obsession to discover and see new places, to face new challenges; it’s the curiosity to uncover new wonders.

This is why we share this brief report on a few of the new Canyoning routes we have opened in Costa Rica with the large community of canyoneers and canyoning addicts worldwide.

To describe everything that goes on and all the emotions experienced during a first descent is very hard, if not impossible, but the idea behind this article is to share a few of the experiences and epic moments from our expeditions in Costa Rica.

The first descent of these canyons was no easy task: canyoning in and of itself involves a certain level of risk; and when we’re talking about a first descent and exploration, the risks are tenfold. The area’s unpredictable weather and the remote location of the canyons were our main concerns.

The key to safety was to identify, acknowledge and plan for hazards.

And hazards were many; which is why we dedicated a lot of effort to study and prepare in advance: planning, organizing and coordinating our expeditions well, in order to ensure the success of each first descent project.

We worked on studying the area’s weather, topographic maps, aerial photography, gradients, distances, and planned for estimated timeframes, route lengths, incidents, time required for bolting, planning for the amount of bolting and anchoring gear, exit points, identifying potential escape routes, overall basin analysis, among others.

Despite the many risks, it is truly a privilege to be able to go where no man has gone before, surrounded by pristine, incomparable natural wonders. The feeling of venturing into the unknown, that mix of adrenaline and tension, that urge to know what’s next, is absolutely unique and hard to describe with words.

During a first descent, you just focus on your job, on helping out your team, on making progress… and on getting out.

Speaking of Costa Rica

Costa Rica is a small country in Central America, just 51.100 Km2 (INEC, 2016.), 34.7 % of which are covered by forest (Instituto Tecnológico de Costa Rica, 2007). Located in the Neotropical realm, the weather conditions are tropical. The country’s minimum elevation is 0 m a.s.l. while its maximum is 3,820 m a.s.l.. The country has a central mountain range running northwest to southeast divided in 4 sections, from which most rivers originate, and which in turn pour into two oceans (the Pacific and the Atlantic).

The topographic and geomorphologic characteristics of Costa Rica’s canyons, which are generally sculpted in volcanic deposits, with highly unstable walls, giant blocks of conglomerate, large basalt formations and chaotic combined blocks with a lot of varied forest and foliage.

There are only two seasons: the dry and rainy seasons. The dry-season runs December through April with just a view variations, while the rainy season runs May through November. However, there are many areas where the weather is highly unstable; par for the course in a tropical country. It’s not uncommon to have “cold fronts” of up to a week and a half even smack dab in the middle of the dry season. On certain years the rainy season can be very intense and the rains can cause floods and devastation. Other years the rainfall is more average and rivers retain their regular levels.

An added danger in Costa Rica’s canyons is snakes, of which there are 23 venomous species (Clodomiro Picado Institute, 2016.).

Gata Fiera Canyon

We had been working on our first descent of this canyon in stages, due to its complex nature. It is a remote canyon, with unstable walls in excess of 200 meters, located in an area with highly unpredictable weather.

It is a short yet technical route, approximately 1.8 km in length. Beautiful, spectacular, challenging, intimidating, impressive. A real technical challenge.

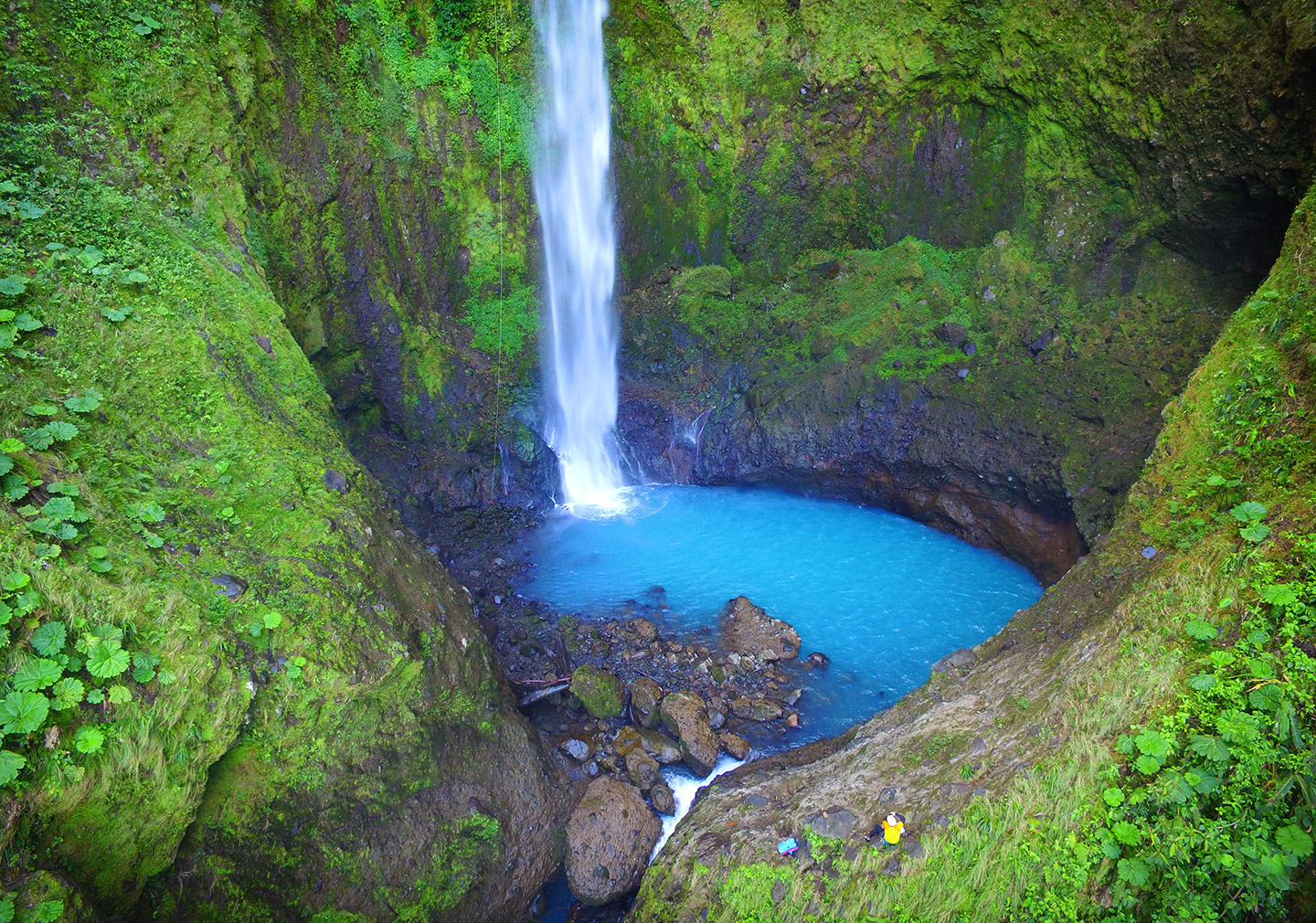

This canyon’s river flows from the extinguished Von Frantzius Volcano. Its waters are dyed an intense light blue/turquoise. These uncanny hues are due to the physical-chemical composition of the water, result of the volcanic deposits and of an optical effect caused by the light. The water’s turquoise colour is absolutely amazing.

According to an article published in the Central American journal of geology (Revista Geológica de América Central) titled “applying a methodology for the assessment of water corrosion of concrete structures” by Vargas & Fernández, 2002; and our own pH tests, the waters of Gata Fiera were found to contain the following:

Comparison of physical-chemical parameters in the Quebrada Gata and Toro rivers

| Lower Quebrada Gata | Toro River | |

|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.11 | 7.22 |

| Na+ (mg/L) | 1.41 | 3.81 |

| K+ (mg/L) | 0.54 | 1.94 |

| Ca+ (mg/L) | 2.56 | 9.93 |

| Mg 2+(mg/L) | 1.06 | 2.95 |

| Fe3- (mg/L) | 0.05 | 0.17 |

| SiO2 (mg/L) | 18.74 | 38.13 |

| SD (mg/L) | 33.58 | 103.2 |

| ST (mg/L) | 38.29 | 108.3 |

| PO4 (mg/L) | 0.09 | 0.08 |

Source: table developed by the author based on data gathered by Vargas & Fernández, 2002.

Another interesting fact is that this canyon was damaged by the Cinchona earthquake of 2009, which is why huge blocks of basalt and conglomerate collapsed into the canyon. It’s a field of huge boulders. Currently the walls look highly unstable.

The team started with the ambitious exploration of this beautiful canyon. Next to the four of us, we could count on the support of two more comrades outside the canyon in case of problems or an emergency.

It was 7 a.m. and the day seemed excellent for canyoning. Observing the intense azure colour of the water at the beginning of the canyon only motivated us more. In the first 500 meters we encountered numerous intense heavenly blue pools. The first waterfall was only five meters high but was preceded by a 10 meter long horizontal slide and the fall ended in a big azure pool.

The sun had disappeared, the sky was getting clouded. As we were progressing we were looking for possible escape routes. We discovered more pools and a waterfall until we arrived at a slide where the water flow was squeezed into a narrow space. Here we visualised a point of escape. Another slightly longer slide came immediately after and ended in a big pool. Once we had descended, we saw we had arrived at the most dangerous and boxed part of the canyon. At 12:20 p.m. we took a look at what was coming ahead: a waterfall of 60 meters with a high water flow, followed by a very squeezed section of unstable walls of 200 to 250 meters high.

Black clouds were gathering up above. We decided to retrieve and not risk being dragged by a flood. It wasn’t a long way back and thanks to good teamwork using human anchor techniques and some climbing we got out of the canyon easily. When we were walking through the dense forest, it started raining heavily. At the exit point we could see the river no longer had an azure colour, it had turned to a muddy brown. Water was pouring in from all sides. It would have been deadly if we had stayed in the canyon with that water level.

23 July 2016

The next day we went back. We started at 6:00 a.m. When we reached the river we noticed that the water still had this chocolate colour and the water level was very high: a ferocious situation. Its intense heavenly blue colour had disappeared. To still make use of the day, we started looking for a way to install a rappel at the edge of the hill in order to see the bottom of the first big descent and the following section more clearly. We threw a line of 100m down to a small bulge where the water level did not reach (this same line was used as an escape route in the fifth attempt). The view was stunning. We had the 220m high waterfall Latas in front of us.

Two comrades descended at the same time, passing grassland and some unstable walls containing loose rocks. We managed to get to the bottom without being swept away by the water. It was drizzling at this time but it didn’t cause any problem. We admired the gorgeous waterfall and we analyzed the line we had to take in a next attempt. It seemed very doable, without any further complications. We started the ascent together. Then the two other comrades descended and climbed up again. A fifth comrade started the descent. But because of the heavy rain he took the decision to not go all the way down to the bottom and return. When we exited the mountain it was about 2 o’clock in the afternoon.

We tried a third time. We were monitoring the weather the entire week before the expedition. The forecast was hopeful. However, when we arrived at the spot on the day of the expedition, the weather on the mountains of Poás and Von Frantzius Volcano wasn’t looking good.

When we had entered the river, some low-hanging clouds were already filling up the sky. We decided to limit our expedition to assessing the pH value of the water. Because of the volcanic origins of the river we were preoccupied about the acidity of the water and its effect on the equipment (ropes, harnesses, carabiners, etc.).

We also took advantage of the time to install the anchor for the first big descent (60m), which is also the entry gate to the most technical and boxed in section, “Garganta del Repisón” (The Big Ledge Gulley). Once you pass this gate there is no turning back nor is there any way of escaping. It is an extremely dangerous stretch of about 200m in between walls that are over 200m high, followed by a multipitch descent of 180m that ends in the Toro river.

Suddenly the weather in the highest parts of the Von Frantzius Volcano changed. This could imply a high risk of floods and danger to the team.

Once we were finished installing the anchorage, we went back using the escape route. We had fixed a rope of 30m at a strategic point to be able to ascend.

2 September 2016

One night before the planned fourth attempt we had dinner together talking about some details concerning the expedition. At 9 p.m. it was time to sleep. We got up at 3 o’clock in the morning to have breakfast and then headed for the canyon. We decided to check the weather forecast one last time before leaving. At this moment we received some sad news: the father of one of our team members had died. We immediately cancelled the expedition.

The rainy season had already arrived. We had to wait until the next dry season, starting in January.

The team was ready for another attempt at “Gata”. As we had already explored the first section, we decided to start the expedition in the final section, “La Garganta del Repisón”, the most dangerous and technical one.

We had studied this complicated section using the images taken by a drone and so we had an idea of what was still to come: a multipitch descent of about 180m. We installed a fixed rope of 120m, that could serve as an escape route, at the place where we had descended the second attempt. After all we didn’t know if the quality of the rock would allow us to make several anchorage points. And also taking into account the force of the water and the height of the canyon.

A comrade was on standby on the highest part of the Poás Volcano to inform us on the weather conditions there. We also had a drone overlooking the canyon from the point where we had installed the escape route.

The final stretch of Gata Baja is formed by a huge canyon, enclosed between two unstable walls of 200 to 300m high. It is a chaos of blocks, giant conglomerate rocks and enormous patches of virgin forest. The geomorphology of these walls is formed mainly by volcanic and basalt rock. It is a short stretch of about 500m which consists of a waterfall of 60m, technical descents, a multipitch descent of 135m divided into four stages (11, 32, 12 and 80m) that ends in a gigantic ledge and from which the final 52m downhill start.

This final descent ends in the rapids of the Toro river. The water of this river tends to be a bit acid and so it can cause irritation to the eyes, though bearable. Another effect is that it tastes like lemonade. A geological brutality.

When we analysed the aerial images of the drone we observed that in this part of the canyon the quality of the rocks was very bad and it wouldn’t permit us to drill an anchorage nor did it show any good natural anchor points. The rocks at the left side followed a line towards the strong current, which made it very dangerous. So we were unsure whether it was even possible to do the multipitch descent.

At 6.30 a.m. we started the hike through the forest. We had to rappel 30m to arrive to the entry gate of the complicated section of Gata Fiera. At 8.05 a.m. we were descending the first waterfall of 60m. This time our team consisted of four members. At 10.30 a.m. we were standing at the top of the multipitch descent of 135m. We decided to call it “La Garganta del Repisón”. We found good quality rocks to drill into and the weather was nice. We took time to drink some water, eat a sandwich, nuts, chocolates and sweets. At 11.30 a.m. we were installing the first anchorage of the multipitch descent. Once secured the first comrade went down to assess the real height of the descent and to analyse if it was possible to put more anchors, to avoid getting trapped halfway.

After a few minutes he ascended with a big smile on his face. He told us that there was a way to put an anchor stage downwards and that the rocks were of good quality. Next to this he told us that there was a small ledge where we could work more comfortably on the anchorage.

At that time there were darker clouds gathering in the sky above, which worried us. Using a radio, we communicated with the team mate located in the upper parts of the Poás Volcano. He told us that there was indeed a very high possibility of rainfall. We decided to abort mission and turn back to the lifeline of 120m we had installed.

Each team member took about 45 to 50 minutes to ascend. The last one was out of the canyon at 6 p.m. A short break refuelling us with energy, drinking water and a snack, was necessary before taking on the climb up the mountain. Nightfall was coming. We had to put on our headlights and force our way through the dense and dangerous forest. We encountered short exposed climbs and big cavities in the ground. Another danger were the poisonous snakes. Most of them are nocturnal and in this area you can find the largest and most poisonous of Costa Rican snakes (the Fer-de-Lance, the jumping viper and the Central American bushmaster).

After almost two hours we did it, we got out. It was 8:10 at night.

21 January 2017

Finally we managed to finish the entire stretch of Gata Fiera. It was a beautiful day and the chances of rainfall were very low according to three different weather forecasts. The expedition lasted from 6.30 a.m. to 6.30 p.m.: 12 hours full of canyoning.

The starting point was the most technical and boxed in section, but now we left out the lifeline. We were determined to finish it until the end and that nothing could go wrong.

At 7.52 a.m. we were rappelling the first waterfall of 60m. All five team members descended safely. At 10.05 a.m. we were drilling the second anchorage of the multipitch descent. We took some time to drink water and eat something. At 11.40 a.m. we had installed the third anchor point. We descended until a big ledge.

The good weather lasted for five hours, but around midday dark clouds started coming in, rain was coming.

At 12.35 p.m. we were ready to install the fourth anchor point. At that moment everything changed. The drill stopped working halfway a multipitch descent of 180m. On top of that it started to rain.

We started to pierce the rock with a hammer and chisel to be able to install the anchorage. After a few minutes the rain stopped. We tried the drill again and it worked, hardly, but it worked.

We threw the rope down the last rappel. We estimated a line of 60m was going to be long enough, but it wasn’t the case. We ran about 20m short to reach the giant ledge.

The first team mate who descended started to look for a spot where we could drill a fifth anchor in order to solve this problem.

After a few minutes he informed us by radio that he had found a secure part in the rock to install the fifth anchor point. There was one problem however, the drill broke down again. We had to think very fast. Were we going to prepare ourselves to spend the night on the ledge? Or lower two of us to drill an anchor by hammer and chisel (which would be complicated and would take a long time)? Or leave the ropes and some more equipment, knowing that there were two more waterfalls to come?

All of a sudden a fourth (and best) option came to mind: to use 20m of the 8mm-line to install the last anchor at the end of this line and then leave it behind. We managed to adjust the length of the rope for the next to last multipitch of the 180m.

This technique allowed us to finish the multipitch without leaving behind any ropes.

This next to last descent was an exciting and intense one: you had to switch ropes on a small ledge of about 50x50cm. At the base there was a big ledge full of giant rocks. We were standing on this ledge at the top of the last rappel at 4.42 in the afternoon. We retrieved the ropes and took some pictures.

At around 5 p.m. we were starting the final descent of 50m.

Because the drill had died, we had to use a large rock to make an anchor point using tubular webbing. It was important to look for a good landing line to avoid problems retrieving the rope. After all, this final rappel ended in the acid waters of the Toro river. Several tributary streams join this river: Río Gorrión, Río Anonos, Río Desagüe and mainly Río Agrio. The latter has a pH of 2.3 and is the reason why there is a considerable white water flow in Río Toro.

It was a very nice descent in between four waterfalls, with a stunning combination of colours: reddish rocks, strips of light green and gold yellow rocks.

At the end of the rappel, the acidity of the water caused a small but bearable burning in the eyes. Because of the acid water the rocks and all organic material had a yellowish colour.

At 5.40 p.m. we were ready to walk the final 600m until the exit point. At 6.35 p.m. we had finished the expedition. After a lot of attempts, we had finally made it. As in mountaineering and climbing you often need more than one attempt. The same rule applies for canyoning.

Mutual trust is critical in a team. “The team is an essential factor to succeed whatever goal or project.” Reinhold Messner.